NumPy, one of the most popular Python libraries for both data science and scientific computing, is pretty omnivorous when it comes to data types: it can handle just everything.

It has its own set of ‘native’ types which it is capable of processing at full speed, but it can also work with pretty much anything known to Python.

The article is written as a supplement to my NumPy Illustrated guide and consists of seven parts:

1. Integers

2. Floats (including Fractions and Decimals)

3. Bools

4. Strings

5. Datetimes

6. Combinations thereof

7. Type Checks

1. Integers

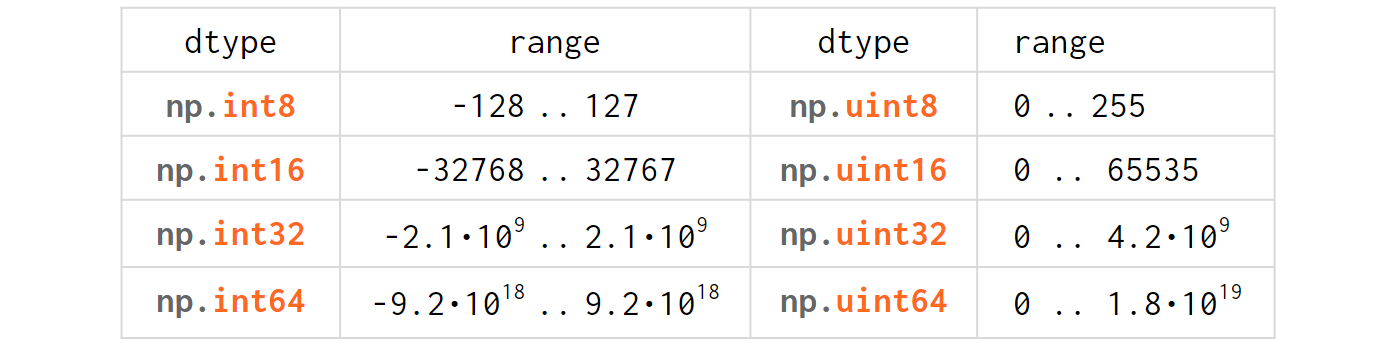

The integer types table in NumPy is absolutely trivial for anyone with minimal experience in C/C++:

Just like in C/C++, u stands for 'unsigned' and the digits represent the number of bits used to store the variable in memory (eg int64 is a 8-bytes-wide signed integer).

When you feed a Python int into NumPy, it gets converted into a native NumPy type called np.int32 (or np.int64 depending on the OS, Python version and the magnitude of the initializers):

>>> np.array([1, 2, 3]).dtype dtype('int32') # int32 on Windows, int64 on Linux and MacOS

If you’re unhappy with the 'flavor' of the integer type that NumPy has chosen for you, you can specify one explicitly: np.array([1,2,3], np.uint8) or np.array([1,2,3], 'uint8').

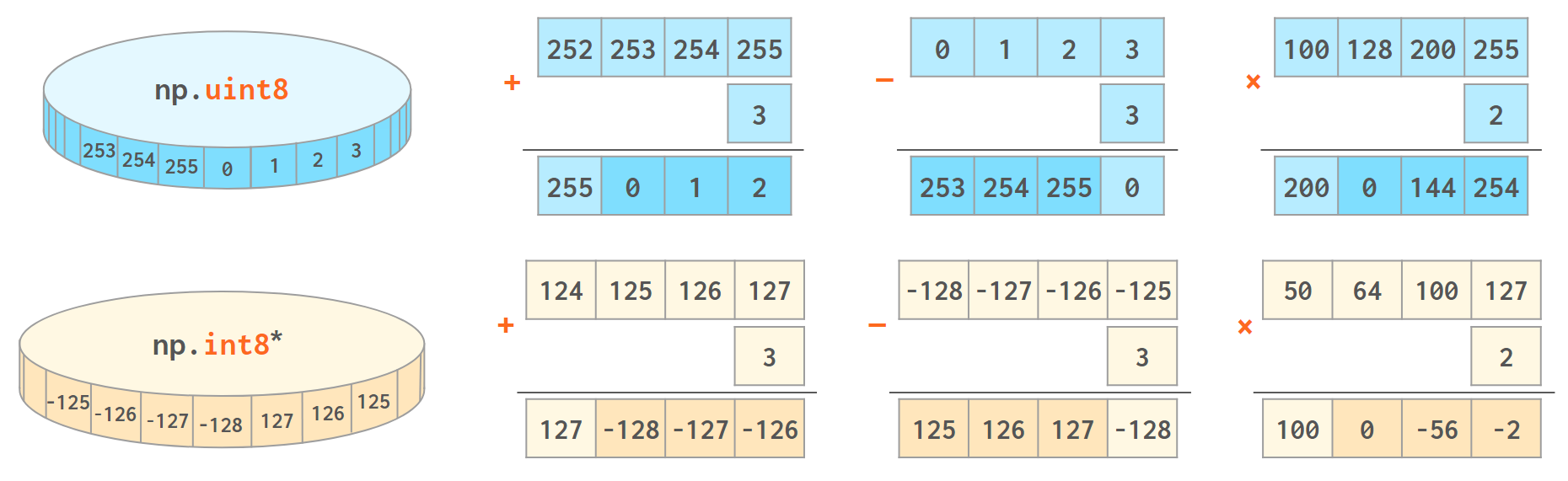

NumPy works best when the width of the array elements is fixed. It is faster and takes less memory, but unlike an ordinary Python int (that works in arbitrary precision arithmetic), the value will wrap when it crosses the maximum (or minimum) value for the corresponding data type:

* Strictly speaking, the C standard defines this wraparound only for unsigned integers; the overflow behavior for signed integers is undefined and can’t be relied upon (in both C and NumPy). Signed integers are silently wrapped around now, but there’s no guarantee they always will.

>>> np.array([255], np.uint8) + 1 # 2**8-1 is INT_MAX for uint8 array([0], dtype=uint8) >>> np.array([2**31-1]) # 2**31-1 is INT_MAX for int32 array([2147483647]) >>> np.array([2**31-1]) + 1 # or np.array([2**31-1], np.int32)+1 on linux array([-2147483648]) >>> np.array([2**63-1]) + 1 # always np.int64 since v > 2**32-1 array([-9223372036854775808])

— not even a warning here!

With scalars, it is a different story: first NumPy tries its best to promote the value to a wider type, then, if there is none, fires the overflow warning (to avoid flooding the output with warnings—only once):

>>> np.array([255], np.uint8)[0] + 1 # ok, promoted to int32(win)/int64(linux) 256 >>> np.array([2**31-1])[0] + 1 # warning! RuntimeWarning: overflow encountered in long_scalars -2147483648 >>> np.array([2**63-1])[0] + 1 # ok, warned already -9223372036854775808

The reasoning behind such a discrimination is like this:

Unlike true floating point errors (where the hardware FPU sets a flag whenever it does an atomic operation that overflows), we need to implement the integer overflow detection ourselves. We do it on the scalars, but not arrays because it would be too slow to implement for every atomic operation on arrays. Robert Kern, one of the NumPy core developers

You can turn it into an error:

>>> with np.errstate(over='raise'): >>> print(np.array([2**31-1])[0]+1) FloatingPointError: overflow encountered in long_scalars

(although the name FloatingPointError for an integer overflow looks a bit misleading.)

... or suppress it entirely:

>>> with np.errstate(over='ignore'): >>> print(np.array([2**31-1])[0]+1) -2147483648

But you can’t expect it to be detected when dealing with arrays (even with the 0-dimensional ones!).

NumPy also has a bunch of C-style aliases (eg. np.byte np.int8, np.short=np.int16, np.intc=int whichever width it has in C etc), but they are getting gradually phased out (eg deprecation of np.long in NumPy v1.20.0) as 'explicit is better than implicit' (but see a present-day usage of np.longdouble below).

And yet some more exotic aliases:

- np.int_ is np.int32 on 64bit windows but int64 on 64bit linux, used to designate the 'default' int. Specifying np.int_ (or just int) as a dtype means "do what you would do if I didn't specify any dtype at all": np.array([1,2]), np.array([1,2], np.int_) and np.array([1,2], int) are all the same thing.

- np.intp is np.int32 on 32bit python but np.int64 on 64bit python, ≈ssize_t in C, used in Cython as a type for pointers.

Occasionally it happens that some values in the array display anomalous behavior or missing, and you want to process the array without deleting them (eg there's some valid data in other columns).

You can't put None there because it doesn't fit in the consecutive np.int64 values and also because 1+None is an unsupported operation.

Pandas has a separate data type for that, but NumPy's way of dealing with the missed values is through the so-called masked array: you mark the invalid values with a boolean mask and then all the operations are carried out as if the values are not there.

>>> np.array([4,0,6]).mean() # the value 0 means 'missing' here 3.3333333333333335 >>> import numpy.ma as ma >>> ma.array([4,0,6], mask=[0,1,0]).mean() 5.0

Finally, if for some reason you need arbitrary-precision integers (Python ints) in ndarrays, NumPy is capable of doing that, too:

>>> a = np.array([10], dtype=object) >>> len(str(a**1000)) # '[1000...0]' 1003

— but without the usual speedup as it will have to store references instead of the numbers themselves, keep boxing/unboxing Python objects when processing, etc.

2. Floats

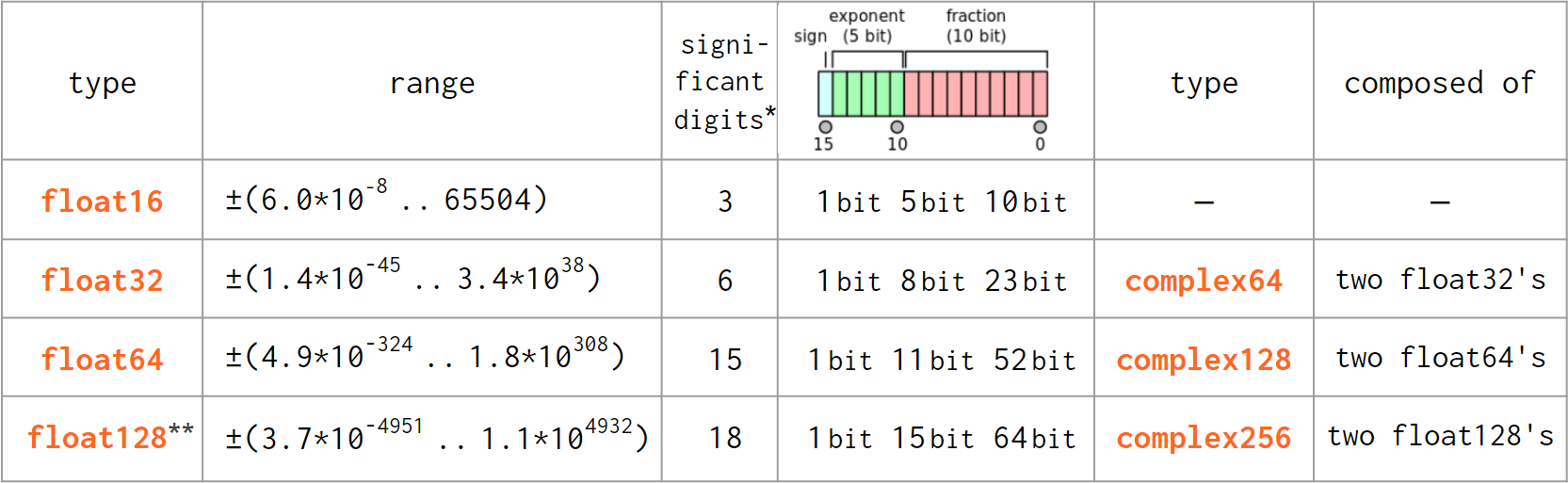

As Python did not diverge from the IEEE 754-standardized C double type, the floating type transition from Python to NumPy is pretty much hassle-free:

* As reported by np.finfo(np.float<nn>).precision. Two alternative definitions give 15 and 17 for np.float64, 6 and 9 for np.float32, etc.

** As of today, np.float128 is Unix-only (not available on Windows).

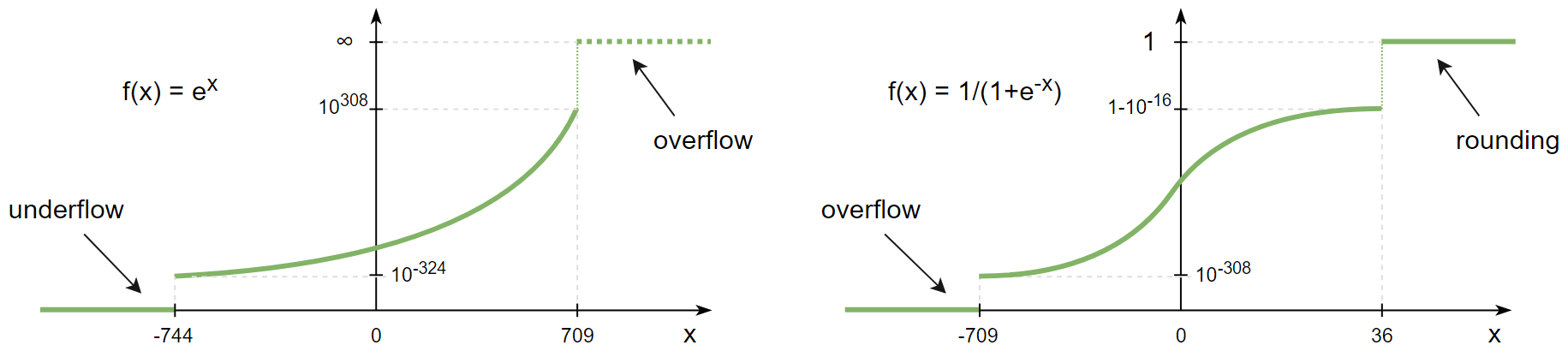

Like integers, floats are also subject to overflow errors.

Suppose you're calculating a sigmoid activation function of the array and one of its element happens to be

>>> x = np.array([-1234.5]) >>> 1/(1+np.exp(-x)) RuntimeWarning: overflow encountered in exp array([0.]) >>> np.exp(np.array([1234.5])) RuntimeWarning: overflow encountered in exp array([inf])

What this warning is trying to tell you is that NumPy is aware that mathematically speaking 1/(1+exp(-x)) can never be zero, but in this particular case due an overflow it is.

Such warnings can be 'promoted' to exceptions or silenced via the errstate or filterwarnings as described in the 'integers' section above - and maybe for this particular case that would be enough - but if you really want to get the exact value you can select a wider dtype:

>>> x = np.array([-1234.5], dtype=np.float128) >>> 1/(1+np.exp(-x)) array([7.30234068e-537], dtype=float128)

Just like in pure Python, NumPy floats exactly represent integers—but only below a certain level (limited by the number of the significant digits):

>>> a = np.array([2**24], np.float32); a # 2^(mantissa_bits+1) array([16777216.], dtype=float32) >>> a+1 array([16777216.], dtype=float32) >>> 9279945539648888.0+1 # for float64 it is 2.**53 9279945539648888.0 >>> len('9279945539648888') # Don't trust the 16th decimal digit! 16

Also exactly representable are fractions like 0.5, 0.125, 0.875 where the denominator is a power of 2 (0.5=1/2, 0.125=1/8, 0.875 =7/8, etc).

Any other denominator will result in a rounding error so that 0.1+0.2!=0.3. The standard approach of dealing with this problem is to compare them with a relative tolerance (to compare two non-zero arguments) and absolute tolerance (if one of the arguments is zero). For scalars, it is handled by math.isclose(a, b, *, rel_tol=1e-09, abs_tol=0.0), for NumPy arrays there’s a vectorized version np.isclose(a, b, rtol=1e-05, atol=1e-08). Note that the tolerance arguments have different names and defaults.

For the financial data decimal.Decimal type is handy as it involves no tolerances at all:

>>> from decimal import Decimal as D >>> a = np.array([D('0.1'), D('0.2')]); a array([Decimal('0.1'), Decimal('0.2')], dtype=object) >>> a.sum() # == Decimal('0.3'), exactly Decimal('0.3')

But Decimal type is not a silver bullet: it also has rounding errors. The only problem it solves is the exact representation of decimal fractions that humans are so used to. Plus it doesn’t support anything more complicated than arithmetic operations and a square root and runs slower than floats.

For pure mathematical calculations fractions.Fraction can be used:

>>> from fractions import Fraction >>> a = np.array([1, 2]) + Fraction(); a array([Fraction(1, 1), Fraction(2, 1)], dtype=object) >>> a/=10; a array([Fraction(1, 10), Fraction(1, 5)], dtype=object) >>> a.sum() Fraction(3, 10)

It can represent any rational number, but pi and exp are out of luck )

Both Decimal and Fraction are not native types for NumPy but it is capable of working with them with all the niceties like multi-dimensions and fancy indexing, albeit at the cost of slower processing speed than that of native ints or floats.

Complex numbers are treated the same way as floats. There are a couple of convenience functions with intuitive names like np.real(z), np.imag(z), np.abs(z), np.angle(z) that work on both scalars and arrays as a whole. The only difference from pure Python complex is that np.complex_ does not work with integers:

>>> np.array([1+2j]) # .dtype == np.complex128 array([1.+2.j])

Just like with the integers, in float (and complex) arrays it is also sometimes useful to treat certain values as 'missing'. Floats are better suited for storing anomalous data: they have a math.nan (or np.nan or float('nan')) value which can be stored inline with the 'valid' numeric values.

But nan is contagious in the sense that all the arithmetic with nan results in nan.Most common statistical functions have a nan-resistant version (np.nansum, np.nanstd, etc), but other operations on that column or array would require prefiltering. Masked arrays automate this step: the mask can only be built once, then it is 'glued' to the original array so that all subsequent operations only see the unmasked values and operate on them.

>>> a = np.array([4., np.nan, 6.]) >>> a.mean() nan >>> a.nanmean() 5.0 >>> a[~np.isnan(a)].mean() 5.0 >>> ma.array(a, mask=[0,1,0]).mean() # nan is not required here, could be anything 5.0

Also the names float96/float128 are somewhat misleading. Under the hood it is not __float128 but whichever longdouble means in the local C++ flavor. On x86_64 Linux it is float80 (padded with zeros for memory alignment) which is certainly wider than float64, but it comes at the cost of the processing speed. Also you risk losing precision if you inadvertently convert to Python float type. For better portability it is recommended to use an alias np.longdouble instead of np.float96 / np.float128 because that's what will be used internally anyway.

More insights on floats can be found in the following sources:

• short and nicely illustrated ‘Half-Precision Floating-Point, Visualized’ [2]

— eg What’s the difference between normal and subnormal numbers?

• more lengthy but very to-the-point, a dedicated website ‘Floating point guide’ [3]

— eg Why 0.1+0.2!=0.3?

• long-read, a deep and thorough What Every Computer Scientist Should Know About Floating-Point Arithmetic, Appendix D [4]

— eg What’s the difference between catastrophic vs benign cancellation?

3. Bools

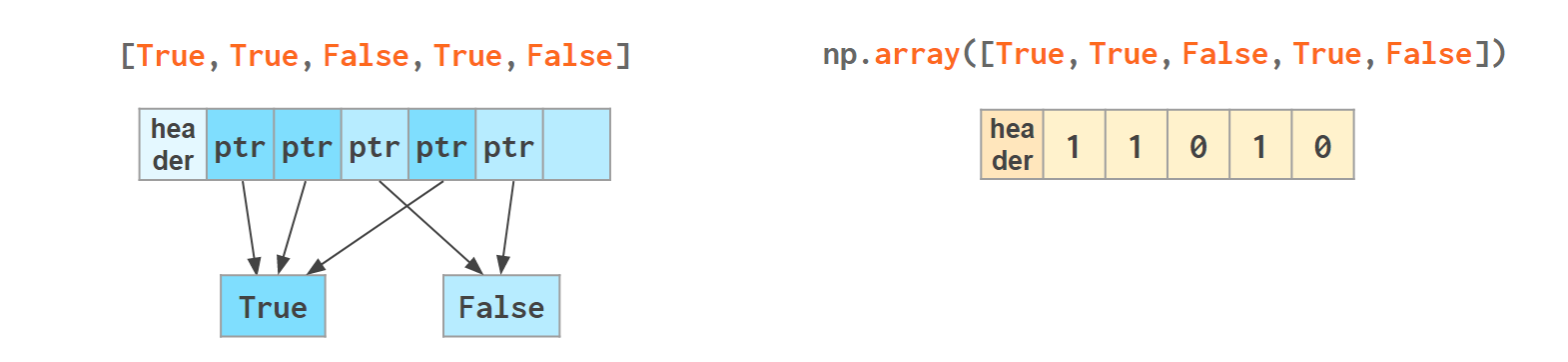

The boolean values are stored as single bytes for better performance. np.bool_ is a separate type from Python’s bool because it doesn’t need reference counting and a link to the base class required for any pure Python type. So if you think that using 8 bits to store one bit of information is excessive look at this:

>>> sys.getsizeof(True) 28

np.bool is 28 times more memory efficient than Python’s bool ) – though in real-world scenarios the rate is lower: when you pack NumPy bools into an array, they will take 1 byte each, but if you pack Python bools into a list it will reference the same two values every time, costing effectively 8 bytes per element on x86_64:

The underlines in bool_, int_, etc are there to avoid clashes with Python’s types. It’s a bad idea to use reserved keywords for other things, but in this case it has an additional advantage of allowing (a generally discouraged, but useful in rare cases) from NumPy import * without shadowing Python bools, ints, etc. As of today, np.bool still works but displays a deprecation warning.

4. Strings

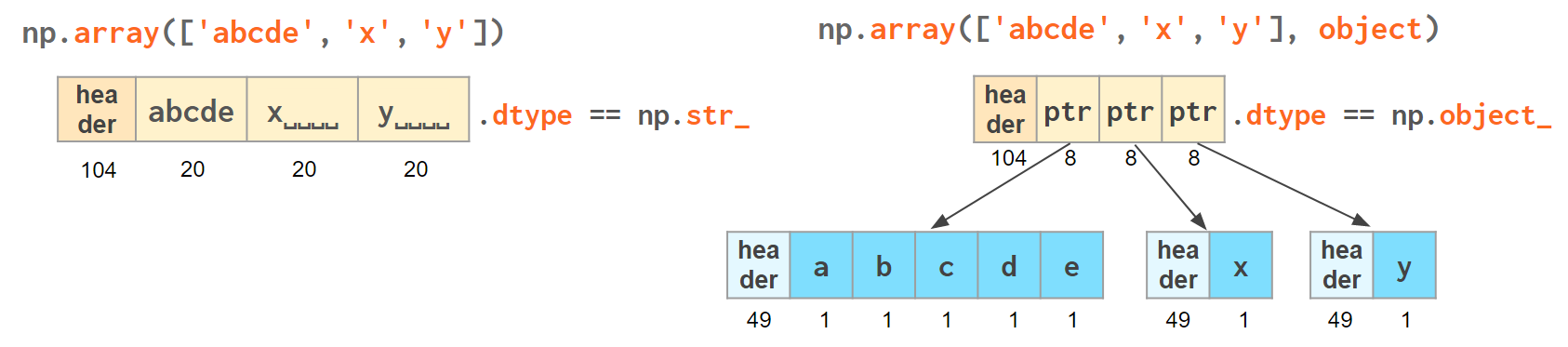

Initializing a NumPy array with a list of Python strings packs them into a fixed-width native NumPy dtype called np.str_. Reserving a space necessary to fit the longest string for every element might look wasteful (especially in the fixed USC-4 encoding as opposed to ‘dynamic’ choice of the UTF width in Python str)

>>> np.array(['abcde', 'x', 'y', 'x']) # 4 bytes per any character array(['abcde', 'x', 'y', 'x'], dtype='<U5') # => 5*4 bytes per element

The abbreviation ‘<U4’ comes from the so called array protocol introduced in 2005. It means ‘little-endian USC-4-encoded string, 5 elements long’ (USC-4≈UTF-32, a fixed width, 4-bytes per character encoding). Every NumPy type has an abbreviation as unreadable as this one, luckily have they adopted human-readable names at least for the most used dtypes.

Another option is to keep references to Python strs in a NumPy array of objects:

>>> np.array(['abcde', 'x', 'y', 'x'], object) # 1 byte per ascii character array(['abcde', 'x', 'y', 'x'], dtype=object) # => 49+len(el) per element

The first array memory footprint amounts to 164 bytes, the second one takes 128 bytes for the array itself + 154 bytes for the three python strs:

Depending on the relative lengths of the strings and the number of the repeated string either one approach can be a significant win or the other.

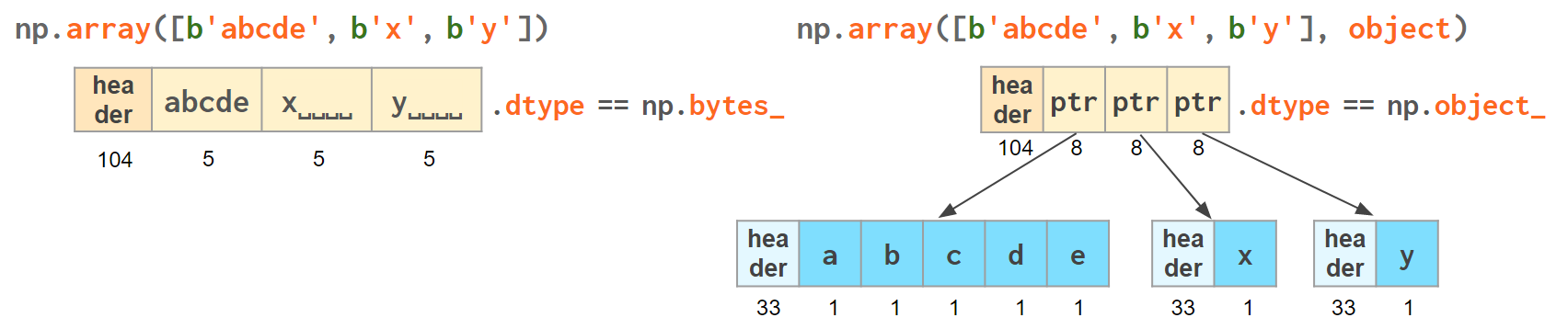

If you're dealing with a raw sequence of bytes NumPy has a fixed-length version of a Python bytes type called np.bytes_:

>>> np.array([b'abcde', b'x', b'y', b'x']) # 1 byte per ascii character array([b'abcde', b'x', b'y', b'x'], dtype='|S5') # => 5 bytes per element

Here |S5 means ‘endianness-unappliable sequence of bytes 5 elements long’.

Once again, an alternative is to store the Python bytes in the NumPy array of objects.

>>> np.array([b'abcde', b'x', b'y', b'x'], object) # 1 byte per ascii character array([b'abcde', b'x', b'y', b'x'], dtype=object) # => 33+len(el) per element

This time the first array takes 124 bytes, the second one is the same 128 bytes for the array itself + 106 bytes for the three python bytes:

We see that str_ is smaller again, yet for more diverse lengths str can take the win.

As for the native np.str_ and np.bytes_ types, NumPy has a handful of common string operations. They mirror Python's str methods, live in the np.char module and operate over the whole array:

>>> np.char.upper(np.array([['a','b'],['c','d']])) array([['A', 'B'], ['C', 'D']], dtype='<U1')

With object-mode strings the loops must happen on the Python level:

>>> a = np.array([['a','b'],['c','d']], object) >>> np.vectorize(lambda x: x.upper(), otypes=[object])(a) array([['A', 'B'], ['C', 'D']], dtype=object)

According to my benchmarks, basic operations work somewhat faster with str than with np.str_.

5. Datetimes

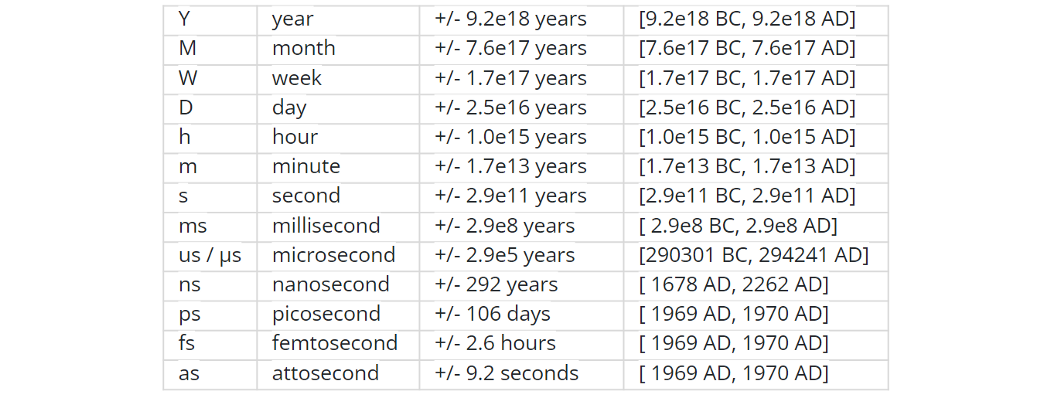

NumPy introduces an interesting native data type for datetimes, similar to a POSIX timestamp (aka Unix time, the number of seconds since the midnight of 1 Jan 1970) but capable of counting time with a configurable granularity - from years to attoseconds - represented invariably by a single int64 number.

Table from the official docs

- Years granularity means 'just count the years' - no real improvement against storing years as an integer.

- Days granularity is an equivalent of Python's datetime.date.

- Microseconds - of Python's datetime.datetime.

And everything below is unique to np.datetime64.

When creating an instance of np.datetime64, NumPy chooses the most coarse granularity that can still hold such data:

>>> np.datetime64('today') # days granularity (in local time UTC+7) numpy.datetime64('2021-12-25') >>> np.datetime64('now') # seconds granularity (in UTC) numpy.datetime64('2021-12-24 18:14:00') >>> np.datetime64(dt.utcnow()) # microsecond granularity numpy.datetime64('2021-12-24 18:14:23.404438') >>> np.datetime64('2021-12-24 18:14:23.404438123') # nanosecond granularity numpy.datetime64('2021-12-24 18:14:23.404438123')

Note that the string initializer is not so lenient as in pd.to_datetime: it must be in this exact format or minimal variations thereof (see 'general principles' of ISO 8601 Wikipedia page). When creating an array you decide if you are ok with the granularity that NumPy has chosen for you or you insist on, say, nanoseconds or what not, and it'll give you 2⁶³ equidistant moments measured in the corresponding units of time to either side of 1 Jan 1970.

>>> np.datetime64(dt.utcnow(), 'datetime64[ns]') # us is too coarse for me! numpy.datetime64('2021-12-24 18:14:23.404438000', dtype='datetime64[ns]')

It is possible to have a multiple of a base unit. For example, if you only need a precision of 0.1 sec, you don't necessarily need to store milliseconds:

>>> a = np.array([dt.utcnow()], dtype='datetime64[100ms]'); a array(['2022-12-24T18:15:08.300'], dtype='datetime64[100ms]') >>> a + 1 array(['2022-12-24T18:15:08.400'], dtype='datetime64[100ms]')

To get a machine-readable representation of the dtype without parsing the string:

>>> a[0].dtype dtype('<M8[100ms]') >>> np.datetime_data(a[0]) ('ms', 100)

Just like in pure Python when you subtract one np.datetime64 from another you get a np.timedelta64 object (also represented as a single int64 with a configurable granularity). For example, to get the number of seconds until the New Year,

>>> z = np.datetime64('2022-01-01') - np.datetime64(dt.now()); z numpy.timedelta64(295345588878,'us') >>> z.item() # constructing an ordinary timedelta, works with datetime64 too datetime.timedelta(3, 36353, 424753) >>> z.item().total_seconds() 295553.424753

Or if you don't care about the fractional part, simply

>>> np.datetime64('2022-01-01') - np.datetime64(dt.now(), 's') numpy.timedelta64(295259,'s')

Once constructed there's not much you can do about the datetime or timedelta objects. For the sake of speed, the amount of available operations is kept to the bare minimum: only conversions and basic arithmetic. For example, there are no 'years' or 'days' helper methods. To get a particular field from a datetime64/timedelta64 scalar you can convert it to a conventional datetime:

>>> np.datetime64('2021-12-24 18:14:23').item() datetime.datetime(2021, 12, 24, 18, 14, 23, 000000) >>> np.datetime64('2021-12-24 18:14:23').item().month 12

For the arrays

>>> a = np.arange(np.datetime64('2021-01-20'), np.datetime64('2021-12-20'), np.timedelta64(90, 'D')); a array(['2021-01-20', '2021-04-20', '2021-07-19', '2021-10-17'], dtype='datetime64[D]')

you can either make conversions between np.datetime64 subtypes (faster)

>>> (a.astype('M8[M]') - a.astype('M8[Y]')).view(np.int64) array([0, 3, 6, 9], dtype=int64)

or use Pandas (2-4 times slower):

>>> s = pd.DatetimeIndex(a); s # or pd.to_datetime(a) DatetimeIndex(['2021-01-20', '2021-04-20', '2021-07-19', '2021-10-17'], dtype='datetime64[ns]', freq=None) >>> s.month Int64Index([1, 4, 7, 10], dtype='int64')

Here's a useful function that decomposes a datetime64 array into an array of 7 integer columns (years, months, days, hours, minutes, seconds, microseconds):

def dt2cal(dt): # allocate output out = np.empty(dt.shape + (7,), dtype="u4") # decompose calendar floors Y, M, D, h, m, s = [dt.astype(f"M8[{x}]") for x in "YMDhms"] out[..., 0] = Y + 1970 # Gregorian Year out[..., 1] = (M - Y) + 1 # month out[..., 2] = (D - M) + 1 # dat out[..., 3] = (dt - D).astype("m8[h]") # hour out[..., 4] = (dt - h).astype("m8[m]") # minute out[..., 5] = (dt - m).astype("m8[s]") # second out[..., 6] = (dt - s).astype("m8[us]") # microsecond return out >>> dt2cal(a) array([[2021, 12, 15, 9, 0, 0, 0], [2021, 12, 18, 9, 0, 0, 0], [2021, 12, 21, 9, 0, 0, 0], [2021, 12, 24, 9, 0, 0, 0]], dtype=uint32)

A couple of gotchas with datetimes:

- Even though leap years are supported,

>>> np.array(['2020-03-01', '2022-03-01', '2024-03-01'], np.datetime64) - \ np.array(['2020-02-01', '2022-02-01', '2024-02-01'], np.datetime64) array([29, 28, 29], dtype='timedelta64[D]')

Leap seconds (essential part of both UTC and ordinary wall time) are not:

>>> np.datetime64('2016-12-31T23:59:60') ValueError: Seconds out of range in datetime string "2016-12-31 12:59:60"

To be fair, neither datetime.datetime nor pytz count them, either (although in general it is possible to extract info about leap seconds from pytz). time module supports them only formally (accepts 60th second, but incorrect intervals).

It looks as if only astropy processes them correctly so far,

>>> from astropy.time import Time >>> (Time('2017-01-01') - Time('2016-12-31 23:59')).sec 61.00000000001593

others adhere to the proleptic Gregorian calendar with its exactly 86400 SI seconds a day that has already gained about half a minute difference with the wall time since 1970 due to irregularities of the Earth rotation. The practical implications of using this calendar are: – mistake when calculating intervals that include one or more leap seconds – exception when trying to construct a datetime64 from a timestamp taken during a leap second

- As both np.datetime64 and np.timedelta64 have the same width, care must be taken with large timedeltas:

>>> np.datetime64('2262-01-01', 'ns') - np.datetime64('1678-01-01', 'ns') numpy.timedelta64(-17537673709551616,'ns')

Finally, note that all the times in np.datetime64 are 'naive': they are not 'aware' of daylight saving (=>it is recommended to store all datetimes in UTC) and are not capable of being converted from one timezone to another (=>use pytz for timezone conversions):

>>> a = np.arange(np.datetime64('2022-01-01 12:00'), np.datetime64('2022-01-03 12:00'), np.timedelta64(1, 'D')) >>> np.datetime_as_string(a) array(['2022-01-01T12:00', '2022-01-02T12:00'], dtype='<U35') >>> np.datetime_as_string(a, timezone='local') array(['2022-01-01T19:00+0700', '2022-01-02T19:00+0700'], dtype='<U39') >>> np.datetime_as_string(a, timezone=pytz.timezone('US/Eastern')) array(['2022-01-01T07:00-0500', '2022-01-02T07:00-0500'], dtype='<U39')

6. Combinations thereof

A 'structured array' in NumPy is a 'two in one' feature: 1) It allows to give names to columns 2) It allows columns to have different data types

If all you need is (1), then you're good to go with just two functions: u2s converts an ordinary ('unstructured') array to structured and s2u converts it back. You have better readability, can use the 'order' argument to 'sort', but be aware that access by name can slow down when done during the iteration in a python loop (operations vectorized on the C level are not affected).

By default the columns are named 'f0', 'f1', etc:

>>> a = np.array([[3,4], [2,7], [1,5], [2,4]]); a array([[3, 4], [2, 7], [1, 5], [2, 4]]) >>> b = u2s(a); b array([(3, 4), (2, 7), (1, 5), (2, 4)], dtype=[('f0', '<i4'), ('f1', '<i4')]) >>> b.sort(order=['f1', 'f0']); b array([(2, 4), (3, 4), (1, 5), (2, 7)], dtype=[('x', '<i4'), ('y', '<i4')]) >>> s2u(b) array([[2, 4], [3, 4], [1, 5], [2, 7]])

It is ok for 'sort', but if you want to do anything else, you might want to give more readable names to the columns:

>>> b = u2s(a, names=['x', 'y']); b

array([(2, 4), (3, 4), (1, 5), (2, 7)], dtype=[('x', '<i4'), ('y', '<i4')])

>>> b['x']

array([2, 3, 1, 2])

>>> b['x'] + b['y']

array([6, 7, 6, 9])

The (2) part is more powerful (and a bit more complicated). Not only can every column have a custom name, but a custom data type, too (akin to struct in C). Any dtype from the previous sections would do (including the object type).

The most straightforward way of building a structured array is to read the data from the csv file and to let NumPy autodetect the dtypes:

a.csv: name, age, height, is_married John, 21, 1.77, True Mary, 20, 1.63, False

>>> np.genfromtxt('a.csv', dtype=None, encoding=None, delimiter=', ', names=True) array([('John', 21, 1.77, True), ('Mary', 20, 1.63, False)], dtype=[('name', '<U4'), ('age', '<i4'), ('height', '<f8'), ('is_married', '?')])

Without dtype=None NumPy will create an ordinary (unstructured) array, parsing all fields as floats and using nans where the conversion fails.

The encoding is a backwards-compatibility artefact. Without it, you'll get bytes instead of strs (and a deprecation warning).

The delimiter must be provided unless the fields are separated by anything other than spaces.

The names of the columns will be automatically filled in from the first line of the csv file. If your csv file doesn't have a header, simply skip 'names=True' argument. If you need to fine-tune a particular name, they are accessible through a.dtype.names. You can also override the names by passing the corresponding list to the 'names' argument to genfromtxt, but it is less convenient because you'll also have to specify skip_header=1.

The cryptic symbols in the dtype are short way to say np.str_ of length 3, np.int32, np.float64, and np.bool_, respectively.

If you already have a python array and want to convert it to a structured array,

>>> a = array([('John', 21, 1.77, True), ('Mary', 20, 1.63, False)]) >>> np.core.records.fromarrays(zip(*a)) rec.array([('John', 21, 1.77, True), ('Mary', 20, 1.63, False)], dtype=[('f0', '<U4'), ('f1', '<i4'), ('f2', '<f8'), ('f3', '?')])

The necessity of transposing the list manually with zip(*a) unnecessarily complicates things (I'd prefer it to be done with a dedicated argument to fromarrays or via a separate constructor). What they were trying to acheive here was the ability to build a structured array from a stack of ordinary arrays:

If you want to fine-tyne the dtypes, you can use the default constructor

Another way to build the structured array is to feed a list of tuples to the constructor directly. This way, you'll have to be explicit about the dtypes, but the abbreviations is not a must, you can use ordinary class names:

>>> a = array([('John', 21, 1.77, True), ('Mary', 20, 1.63, False)], dtype=[('name', 'U4'), ('age', int), ('height', float), ('is_married', bool)])

It might be awkward to list the types manually, but allows you to be specific about the particular types (eg you want to build float column from integer values, or set a wider width of string if you know they are likely to grow in future).

>>> np.core.records.fromarrays([ np.array(['John', 'Mary']), np.array([21, 20]), np.array([1.77, 1.63]), np.array([True, False])]) rec.array([('John', 21, 1.77, True), ('Mary', 20, 1.63, False)], dtype=[('f0', '<U4'), ('f1', '<i4'), ('f2', '<f8'), ('f3', '?')])

A typical example is an RGB pixel color: a 3 bytes long type (usually 4 for alignment), in which the colors can be accessed by name:

>>> rgb = np.dtype([('x', np.uint8), ('y', np.uint8), ('z', np.uint8)]) >>> a = np.zeros(5, z); a array([(0, 0, 0), (0, 0, 0), (0, 0, 0), (0, 0, 0), (0, 0, 0)], dtype=[('x', 'u1'), ('y', 'u1'), ('z', 'u1')]) >>> a[0] (0, 0, 0) >>> a[0]['x'] 0 >>> a[0]['x'] = 10 >>> a array([(10, 0, 0), ( 0, 0, 0), ( 0, 0, 0), ( 0, 0, 0), ( 0, 0, 0)], dtype=[('x', 'u1'), ('y', 'u1'), ('z', 'u1')]) >>> a['z'] = 5 >>> a array([(10, 0, 5), ( 0, 0, 5), ( 0, 0, 5), ( 0, 0, 5), ( 0, 0, 5)], dtype=[('x', 'u1'), ('y', 'u1'), ('z', 'u1')])

To be able to access the fields as attributes, a recarray can be used:

>>> b = a.view(np.recarray) >>> b rec.array([(10, 0, 5), ( 0, 0, 5), ( 0, 0, 5), ( 0, 0, 5), ( 0, 0, 5)], dtype=[('x', 'u1'), ('y', 'u1'), ('z', 'u1')]) >>> b[0].x 10 >>> b.y=7; b rec.array([(10, 7, 5), ( 0, 7, 5), ( 0, 7, 5), ( 0, 7, 5), ( 0, 7, 5)], dtype=[('x', 'u1'), ('y', 'u1'), ('z', 'u1')])

Here it works like reinterpret_cast in C++, but sure enough, recarray can be created on its own, without being a view of something else.

Types for structured dtypes do not necessarily need to be homogenic and can even include subarrays.

With structured arrays and recarrays can get the 'look and feel' of a basic Pandas DataFrame:

– you can address columns by names,

– do some arithmetic and statistic calculations with them,

– some operations are faster in NumPy than in Pandas

but they lack:

– grouping (except what is offered by itertools.groupby)

– the mighty Pandas Index and MultiIndex (so no pivot tables) and

– other niceties like convenient sorting, etc.

The gotcha here is that even though this syntax is convenient for addressing particular columns as a whole, neither structured arrays nor recarrays are something you'd want to use in the innermost loop of a compute-intensive code:

a = np.random.rand(100000, 2) b = a.view(dtype=[('x', np.float64), ('y', np.float64)]) c = np.recarray(buf=a, shape=len(a), dtype= [('x', np.float64), ('y', np.float64)]) s1 = 0 for r in a: s1 += (r[0]**2 + r[1]**2)**-1.5 # reference s2 = 0 for r in b: s2 += (r['x']**2 + r['y']**2)**-1.5 # 5x slower s3 = 0 for r in c: s3 += (r.x**2 + r.y**2)**-1.5 # 7x slower S1 = np.sum((a[:, 0]**2 + a[:, 1]**2)**-1.5) # 20x faster S2 = np.sum((b['x']**2 + b['y']**2)**-1.5) # same as S1 S3 = np.sum((c.x**2 + c.y**2)**-1.5) # same as S1

Note: profiling python code can sometimes be counter-intuitive: changing x**2 to x*x can make the code run 1.5 faster or slower depending on the nature of x.

7. Type Checks

One way to check NumPy array type is to run isinstance against its element:

>>> a = np.array([1, 2, 3]) >>> v = a[0] >>> isinstance(v, np.int32) # might be np.int64 on a different OS True

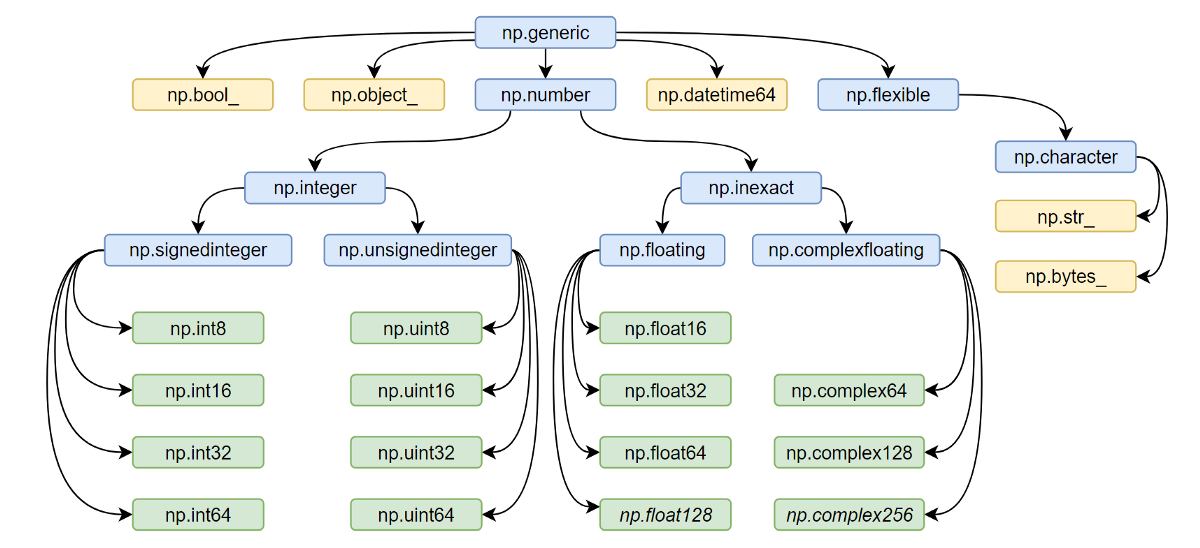

All the NumPy types are interconnected in an inheritance tree displayed at the top of the article (blue=abstract classes, green=numeric types, yellow=others) so instead of specifying a whole list of types like isinstance(v, [np.int32, np.int64, etc]) you can write more compact typechecks like

>>> isinstance(v, np.integer) # true for all integers True >>> isinstance(v, np.number) # true for integers and floats True >>> isinstance(v, np.floating) # true for floats except complex False >>> isinstance(v, np.complexfloating) # true for complex floats only False

The downside of this method is that it only works against a value of the array, not against the array itself. Which is not useful when the array is empty, for example. Checking the type of the array is more tricky.

For basic types the == operator does the job for a single type check:

>>> a.dtype == np.int32 True >>> a.dtype == np.int64 False

and in operator for checking against a group of types:

>>> x.dtype in (np.half, np.single, np.double, np.longdouble) False

But for more sophisticated types like np.str_ or np.datetime64 they don’t.

The recommended way [5] of checking the dtype against the abstract types is

>>> np.issubdtype(a.dtype, np.integer) True >>> np.issubdtype(a.dtype, np.floating) False

It works with all native NumPy types, but the necessity of this method looks somewhat non-obvious: what’s wrong with good oldisinstance? Obviously the complexity of dtypes inheritance structure (they are constructed ‘on the fly’!) didn’t allow to do it according to principle of least astonishment.

If you have Pandas installed, its type checking tools work with NumPy dtypes, too:

>>> pd.api.types.is_integer_dtype(a.dtype) True >>> pd.api.types.is_float_dtype(a.dtype) False

Yet another method is to use (undocumented, but used in SciPy/NumPy code bases, eg here) np.typecodes dictionary. The tree it represents is way less branchy:

>>> np.typecodes {'Character': 'c', 'Integer': 'bhilqp', 'UnsignedInteger': 'BHILQP', 'Float': 'efdg', 'Complex': 'FDG', 'AllInteger': 'bBhHiIlLqQpP', 'AllFloat': 'efdgFDG', 'Datetime': 'Mm', 'All': '?bhilqpBHILQPefdgFDGSUVOMm'}

Its primary application is to generate arrays with specific dtypes for testing purposes, but it can also be used to distinguish between different groups of dtypes:

>>> a.dtype.char in np.typecodes['AllInteger'] True >>> a.dtype.char in np.typecodes['Datetime'] False

Note that using a.dtype.kind instead of a.dtype.char is a mistake: np.zeros(1, dtype=np.uint8).dtype.kind == 'u' is missing from np.typecodes while <…>.char == 'B' is listed there.

One downside of this method is that bools, strings, bytes, objects, and voids ('?', 'U', 'S', 'O', and 'V', respectively) don't have dedicated keys in the dict.

This approach looks more hackish yet less magical than issubdtype.

References

- Ricky Reusser, Half-Precision Floating-Point, Visualized

- Floating point guide https://floating-point-gui.de/

- David Goldberg, What Every Computer Scientist Should Know About Floating-Point Arithmetic, Appendix D

- NumPy issue #17325, Add a canonical way to determine if dtype is integer, floating point or complex

License

CC BY-NC 4.0 (=you share and adapt as long as you give attribution, don’t make money out of it, and keep the same license).